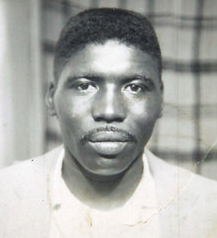

Black History Month: Medgar Evers

February 2, 2023

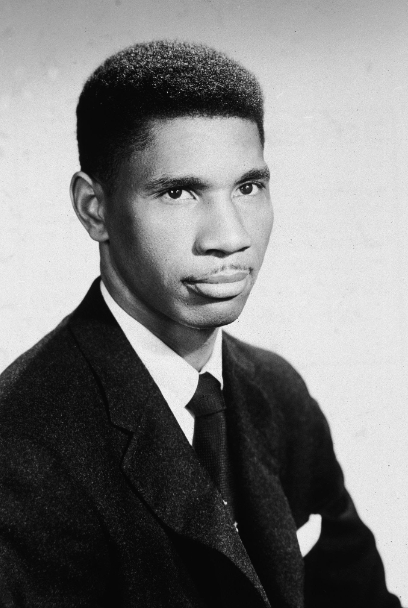

It is February, which means it’s Black History Month, a time to learn about the history and contributions of African Americans in the U.S. Today we focus on Medgar Evers, an activist during the civil rights movement. Let’s look back at his legacy.

Medgar Evers was born on July 2, 1925, in Decatur, Mississippi to James and Jessie Evers. His childhood experiences were not uncommon for Black people who grew up in the Jim Crow South as he faced racism and prejudice on a daily basis. When he was just 12 a family friend of the Evers was lynched. The man’s bloody clothing was left hanging on a fence for over a year as an act of intimidation. During his teen years, Evers would watch white gangs prowl the streets on Saturday nights looking for a black person to beat up or run over with their cars.

These cases of racial prejudice would influence him later in life and made him determined to become something. Evers dropped out of high school at 17 and joined the U.S. army during World War II. He served in a segregated unit in Europe for the majority of his service. In 1946, after three years of service, Evers was released with an honorable discharge. After leaving the army, he finished high school and then enrolled in Alcorn College in Mississippi where he majored in business administration. Alcorn College is where he met Myrlie Beasley, who he would later marry in 1951.

Once he graduated college, Evers and Myrlie moved to Mound Bayou, Mississippi where he found a job selling insurance. In Mound Bayou he witnessed the poverty the black population faced in rural Mississippi. With this in mind, Evers joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Once he joined, Evers organized local NAACP chapters and coordinated boycotts of gas stations that refused to let African Americans use their bathrooms. Evers rose in the NAACP due to his organizational skills and his ability to bring together isolated groups of people.

After the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which outlawed segregation in public schools, Evers applied to the University of Mississippi Law School. After the school, which was still segregated, rejected him, Evers joined the NAACP campaign to desegregate the school. This brought him to the attention of NAACP national leadership who appointed him their first field secretary for the South.

After becoming field secretary, Evers, and his family, moved to Jackson, Mississippi where he started an NAACP office. Throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s, Evers organized boycotts of local merchants and led voter registration drives and peaceful rallies across the state. In 1962 Evers was famously part of the campaign to get African American student James Meredith admitted to the University of Mississippi. Evers played a key role in the campaign, which was successful and became a landmark event in the civil rights movement.

His wife, Myrlie, was also very involved in the civil rights movement and NAACP. She worked as his full-time secretary at the Jackson office and helped do research for his speeches. By the early 1960s death threats against Evers were a regular occurrence, and his name was on many white supremacist death lists. Despite this, Evers continued his work for NAACP and regularly organized rallies, boycotts, and prayer vigils, and helped bail out arrested African Americans.

In early June of 1963, the Evers home was firebombed. This prompted a national address by President John F. Kennedy. President Kennedy addressed the civil rights movement and called white resistance against civil rights a “moral crisis” and pledged federal support for integration. This was another landmark moment in the movement and politics as the President declared his support for civil rights.

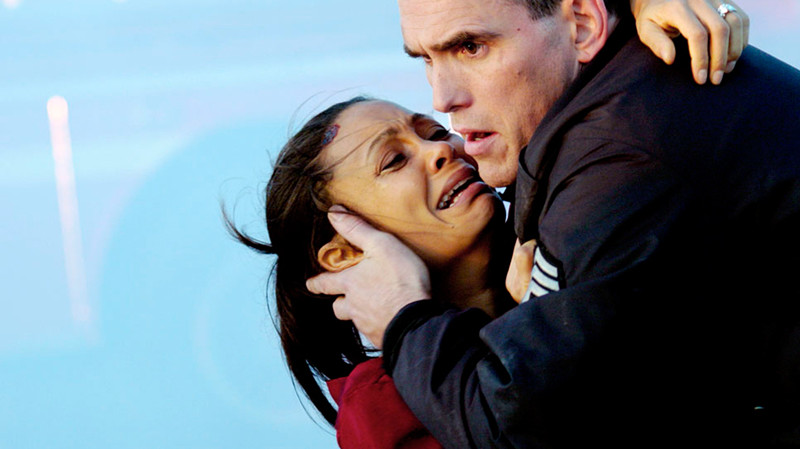

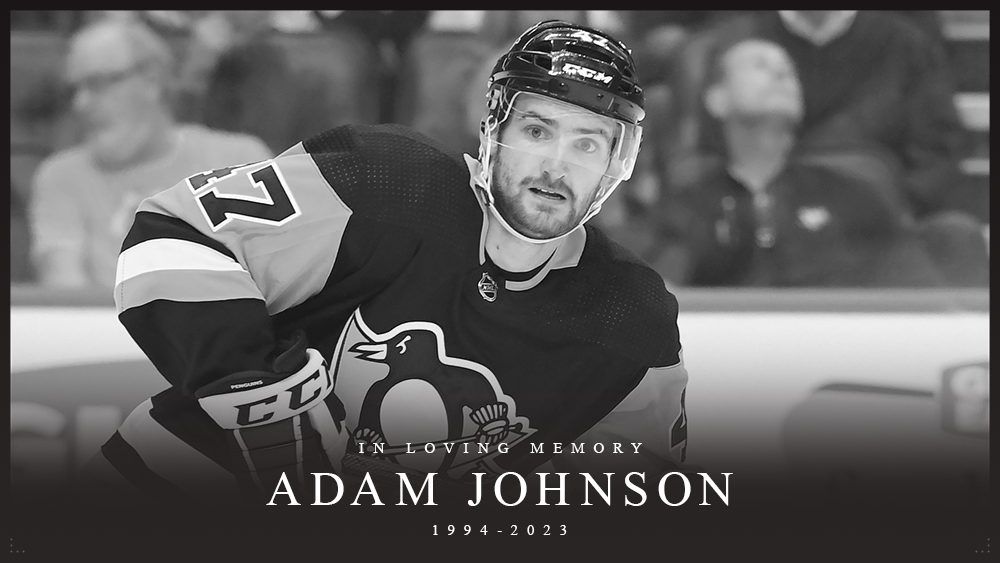

During President Kennedy’s address, Evers was attending an NAACP function. As he returned home around midnight, Evers was hit by a sniper’s bullet on the doorstep of his home. He would be dead 50 minutes later. Medgar Evers was assassinated on June 12, 1963, at the age of 37.

Evers’ death sparked widespread outrage amongst African Americans and the FBI opened an investigation into his murder. They came up with a suspect, white supremacist and Ku Klux Klan member Byron de la Beckwith, whose fingerprints were found on the gun at the murder scene. Later, people would also report that he bragged about killing Evers. De la Beckwith would be tried twice, both times by all-white, all-male juries. Both trials resulted in a hung jury. 31 years later, De la Beckwith would be found guilty by a racially mixed jury on February 5, 1994, and was given a life sentence.

After his death, the NAACP awarded Evers the Spingarn Medal for his services to the black community. His murder would also make Evers a nationally known figure and make him a symbol of the civil rights movement. Evers’ death brought needed attention to the movement and served as an example of the brutality African Americans faced at the time. Evers was buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors and is where he rests today.

Medgar Evers was an integral part of the NAACP and civil rights movement and is a role model for any activist or any rights movement. His bravery and fortitude are an inspiration to the people of today and are a reminder of the struggles of African Americans. To finish on Evers’ own words: “You can kill a man, but you can’t kill an idea.”

Kyle • Feb 12, 2023 at 10:00 pm

Good Article

Grace Garcia • Feb 10, 2023 at 1:39 pm

Very nice article, perfect for Black History Month.

Caroline Forde • Feb 9, 2023 at 12:30 pm

Very well written!

Isabella Hawkins • Feb 7, 2023 at 11:18 am

You did an amazing job! Thank you for educating us on people who helped make a change during the civil rights Movement. Happy BMH!