With the yearly Oscar buzz starting up once again, instead of discussing this year’s snubs and predicted winners, I thought it was about time that we honor some of the Academy’s more… questionable choices over the years.

Whether it be their insistence on wasting time during the broadcast, the monochromatic voters, their aversion to horror and comedy, the way they treat animation, the favoritism towards American films, to the often gargantuan runtimes (in 2022, they cut out 8 categories for the sake of time, and were still unable to keep it under 3 and a half hours), the celebrity drama… there’s a lot to criticize them for.

However, it all leads up to the Best Picture award, which has a mostly solid track record of honoring well-crafted pieces of art, even if they weren’t necessarily the best picture of the year. To its credit, the arguments people get into over Best Picture are often about a film in question being better or worse than another, rather than it being a bad movie overall.

This is not always the case, however.

These are the 10 worst films to ever get Best Picture, in chronological order. Importantly, these films are rated in a vacuum. You won’t see films like Argo, Chicago, Gandhi, or The Last Emperor here, because they aren’t bad films on their own, they just may not have deserved the award given the competition. No, these 10 films are weak no matter what their competition was.

The Broadway Melody (1929)

Other Wins: N/A

What should’ve won: The Passion of Joan of Arc

The Broadway Melody was the second film to ever win Best Picture, and its focus on musical spectacle above all else has not stood the test of time like some of its contemporaries. Outside of some minor historical achievements, there is no reason to watch this mostly charmless pre-Code musical.

Made when sound was still a novelty, the film is mostly a run-through of melodramatic ideas that have been done better in many other pictures. Even its fellow nomination The Hollywood Revue accomplishes what The Broadway Melody was trying to do better than it could even imagine. I don’t particularly think either film is great, but The Broadway Melody is without a doubt the weaker choice. I see no reason why this award didn’t go to the fantastic silent picture The Passion of Joan of Arc, a timeless piece of cinematic brilliance. As for this movie, some lovely set design can’t save a mostly plotless, Vaudevillian bore.

Cimarron (1931)

Other Wins: Best Writing – Adaptation and Best Art Direction

What should’ve won: M

Cimarron features a breakout role for Irene Dunne, padded out with offensive stereotypes, terrible pacing, and a spotty story.

There is a lot to criticize Cimarron for: an unrelatable lead character, dull direction, and offensive depictions of African-Americans, Jews, and Indians. But far and away the biggest problem is its pacing. The film spans nearly four decades over 2 hours, and it feels like nothing happens for long stretches. It feels much longer than it is, and it doesn’t have anything particularly compelling to make up for it.

The only thing Cimarron has going for it is Dunne’s performance and an admittedly pretty impressive opening sequence. Other than that, you’ll just be saving yourself time by skipping this one. As one of only four Westerns to win Best Picture, it’s a pretty disappointing film to represent this monumental genre in cinematic history (especially considering that one of them is arguably an anti-western, No Country for Old Men).

The Greatest Show On Earth (1952)

Other Wins: Best Story

What should’ve won: High Noon or Ikiru

…I don’t know about that.

In theory, The Greatest Show On Earth is a joyous movie. A Technicolor spectacle filled with bright colors, stunning feats, and lavish production design. In execution, however, for reasons beyond me, Cecil B. DeMille managed to turn it into a mostly charmless, two-and-a-half-hour jumble of colorful slop.

This film embodies the worst impulses of 50s filmmaking, with safe, big-budget, corporate, assembly-line pictures pumped out like factory work. There is next to zero artistry to The Greatest Show On Earth, only manufactured so-called “wonder”. Top that off with a wasted cast, a bizarre tone, and almost no coherent story to speak of, this movie would be all but forgotten if it weren’t for its Best Picture win and references in The Fabelmans.

There is a lot of argument as to why Cecil B. DeMille’s atonal nightmare took home the big prize, with most film historians settling on a mix of red-baiting the crew behind High Noon and finally giving Hollywood legend Cecil B. DeMille an award. But if your film is so bad that its win is almost always choked up to inside corruption, then you’ve messed up.

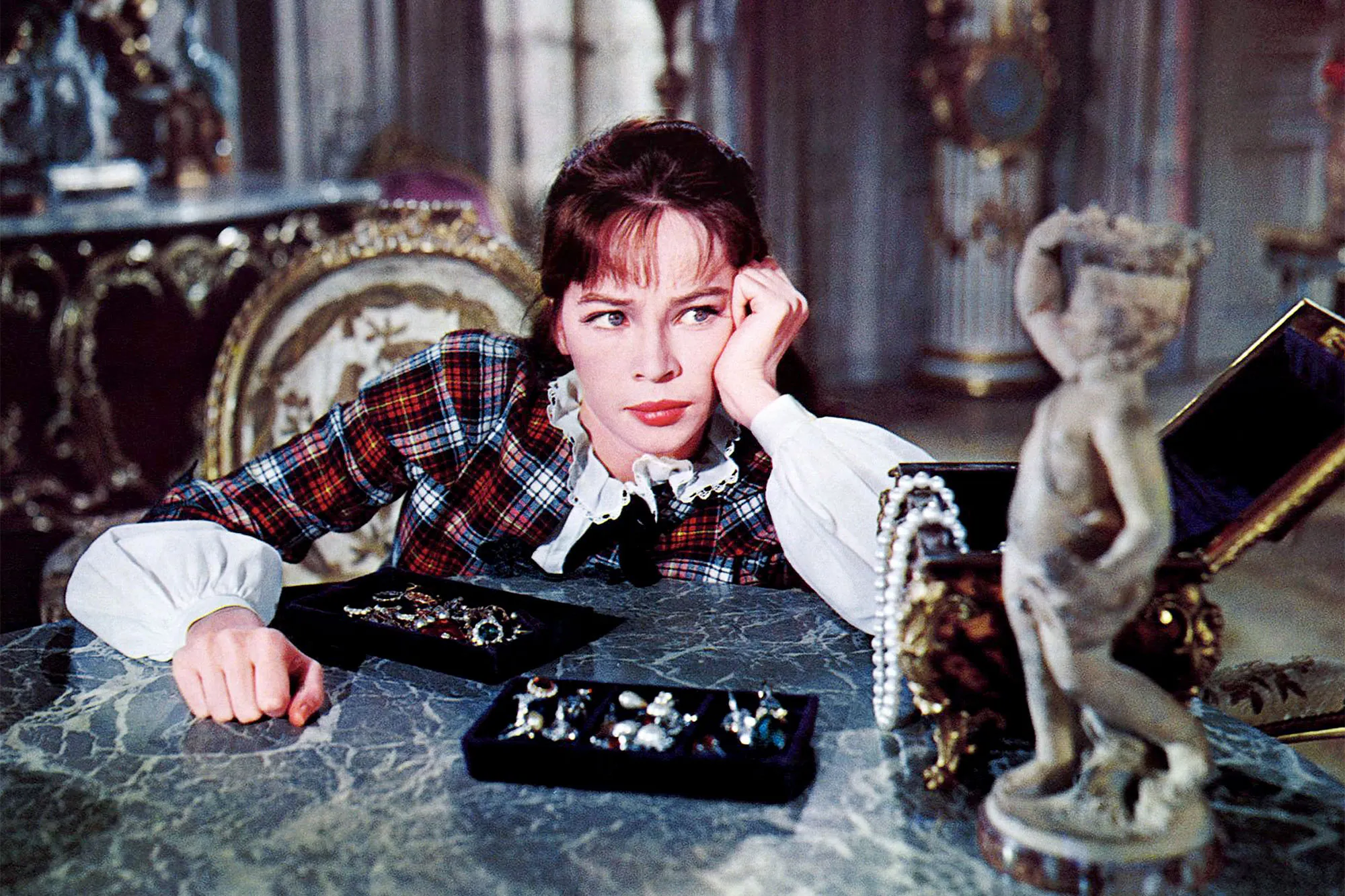

Gigi (1958)

Other Wins: Best Director, Best Screenplay – Based on Material from Another Medium, Best Art Direction, Best Set Decoration, Best Cinematography – Color, Best Costume Design, Best Film Editing, Best Scoring of a Musical Picture, and Best Song

What should’ve won: Vertigo

Gigi is a movie that feels icky and isn’t even good enough to look past its disturbing core premise. About as flat and generic as 50s Hollywood musicals could get, Gigi has some solid performances and production value, but not much else.

When a Parisian playboy (Louis Jourdan) meets the young courtesan Gigi (Leslie Caron), they have a platonic relationship. But as she matures into a woman, she becomes a romantic interest for the playboy, and he is torn between the girl and his blasé lifestyle. Yeah. It’s pretty gross. Not to mention a shockingly predatory opening number that bears the title “Thank Heaven for Little Girls”. Stay classy, Academy.

Not that this story couldn’t be tackled in a realistic and mature way that condemns the main character (see Kubrick’s Lolita film, which knowingly paints a “classic Hollywood” vibe on a predatory relationship for cinematic dissonance), but this film has no interest in doing that. The fact of the matter is that Gigi wasn’t even made long enough ago for this level of chauvinism to be excused, and it is a film that gives you no reason to even attempt to look past it. When you get down to it, this is just a generic, tired Hollywood story that is as amoral as it is lame.

Out of Africa (1985)

Other Wins: Best Director, Best Screenplay – Based on Material from Another Medium, Best Art Direction, Best Cinematography, Best Original Score, and Best Sound

What should’ve won: Ran or Kiss of the Spider Woman

This is a weird one. Out of Africa has tons of good elements: great cinematography, two wonderfully charismatic leads, a sprawling romance, competent direction, and an outstanding score. But the unfortunate truth is that is all that Out of Africa has.

The movie lacks a pulse, a drive to make it worthy of the above-the-line elements it possesses. It isn’t offensive, it isn’t a disaster, it isn’t an incompetent picture, and it is worthy of praise. But it’s just… meh. And I’m not the only one who thinks this way.

It’s surprisingly heartless for a romantic epic film, and the story is melodramatic and Cliché. Additionally, this is yet another film that suffers from its bloated runtime.

To be fair, this is one of the less egregious films on the list. If this list was ranked in descending order, it’s pretty safe to say this would be at the top. It goes down easy, but it’s a lukewarm romance that is in no way deserving of the biggest prize in Hollywood, especially considering its incredible competition.

Driving Miss Daisy (1989)

Other Wins: Best Actress, Best Makeup, and Best Adapted Screenplay

What should’ve won: Do The Right Thing or My Left Foot

This is the first of two forgettable feel-good comedy-drama Best Picture winners which use a driver and a passenger as a metaphor for race relations. There are a few genuine emotional moments in the film, but it twists the story so unnaturally and generically, that they feel contrived rather than powerful.

The film comes from a slight, mild, and ultimately naïve place where race relations in the 1940s are just a roadblock in a blooming friendship. The film’s criticism of the racism of the South is few and far between, and it ultimately reinforces the stereotypes that it hopes to subvert: a rich white employer and a passive, willing black worker. The film attempts to combat violence (both within its setting and the landscape of American cinema) with humanity, but none of the humanity feels earned because the systemic injustices at play are less important than comfortable melodrama.

Outside of the incredible lead actors, there is no reason why this film even deserved a nomination over Do The Right Thing, let alone a win over the much more effective My Left Foot.

Braveheart (1995)

Other Wins: Best Director, Best Cinematography, Best Makeup, and Best Sound Effects Editing

What should’ve won: Casino or Leaving Las Vegas

Mel Gibson’s self-aggrandizing historical epic is an overly long, wildly anachronistic trek through tired Hollywood Anglophobic heroics and senseless, drawn-out violence. An undeniably commendable project in terms of scope crumbles under a weak screenplay and clunky direction.

Braveheart is about the 13th-century Scottish warrior who led the Scots in their first war of independence. This is a film that so desperately wants to stand alongside big rousing Hollywood classics like Spartacus and Ben-Hur but misses the mark with its unfunny jokes, focus on ultra-violence, and bad pacing. And, like Gibson’s films The Passion of the Christ and Hacksaw Ridge, the film is so quick with its obvious religious symbolism, combined with the casual racism and historical inaccuracies of Apocalypto.

It does feature some outstanding cinematography and production design but it is all stuck in what could’ve been an above-average 90-minute historical drama, or an above-average 90-minute character-driven action flick, but instead is a middling three-hour slog.

Considering the year that 1995 was for cinema, it’s difficult to understand why this film beat classics like two sprawling crime masterpieces in Casino and Heat, the snappy and brilliantly cast The Usual Suspects, the heartbreaking drama Leaving Las Vegas, the nail-biting Apollo 13, the unforgettable Se7en, or even Sense and Sensibility.

Shakespeare in Love (1998)

Other Wins: Best Actress, Best Supporting Actress, Best Screenplay – Written Directly for the Screen, Best Art Direction, Best Costume Design, Best Original Musical or Comedy Score

What should’ve won: Saving Private Ryan

Shakespeare in Love might be too clever for its good. A film that, in fleeting moments throughout, showcases an undeniable wit, only making the so-so overall picture much more disappointing than if it was just another period rom-com.

Joseph Fiennes and Gwyneth Paltrow star in a fictional romance between playwright William Shakespeare and the character that he would go on to write about, Viola de Lesseps from The Tempest. In terms of sets, costumes, acting, music, cinematography, and direction, the film is mostly strong, if not a bit bland in some areas. All of the problems come down to the screenplay.

The film is filled with clever winks to the audience. For example, in one interaction, impresario Philip Henslowe says “The show must… you know…” and then trails off, and the next line of dialogue is The Bard urging him to “Go on!” These types of jokes, which are almost non-stop, quickly become tiresome, as you start to question whether or not they add anything substantial to the film.

That sharp wit present in the dialogue is unfortunately lacking in other elements of the screenplay, as the characters (both fictional and real) are little more than vessels for quippy jokes. Surprisingly, for an attempt at a “classy” film, Shakespeare in Love often throws in out-of-place and bizarrely interchangeable sex scenes, presumably to ward away potential boredom or maybe some lost aesthetic fulfillment. As is, it plays like the filmmakers were under the impression that seeing Shakespeare involved in bland, R-rated sex is inherently substantive imagery.

The biggest problem is that when you take out a smart core concept, Shakespeare in Love is not all that original or even interesting. Director David Cronenberg put it best:

“I hate movies that just push all those courtly love buttons and expect to get a response, and of course often they do… That movie [Shakespeare in Love] really annoyed me. Not only is it deconstructionist film-making, but it’s also just Romeo and Juliet again. Really it’s no more. It’s in fact quite a bit less, and part of the reason is it’s courtly love again.”

Excerpt from David Cronenberg: Interviews with Serge Grünberg (2006) Plexus Publishing.

Crash (2004)

Other Wins: Best Original Screenplay and Best Film Editing

What should’ve won: Literally anything else.

The funniest thing about Crash is that not only is it not the greatest motion picture of 2004, nor would it even break the top 10, nor that there were numerous better-made films the same year that tackle similar themes, but that it isn’t even the best movie named Crash. That would go to David Cronenberg’s disturbing NC-17 nightmare from 1996.

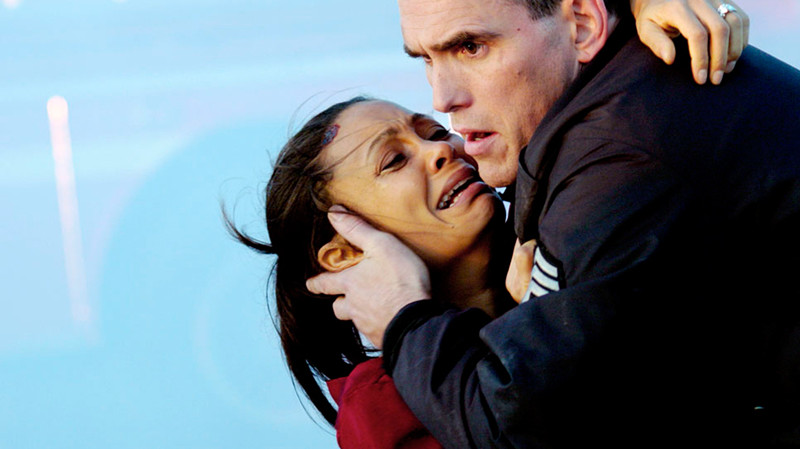

Paul Haggis’ Crash winning Best Picture is still one of the biggest upsets in Oscars history. A dead-on-arrival tale of tensions in post-9/11 America is still laughed at to this day for its simplistic and stupid portrayal of the struggles between classes, races, and genders. A complex jumble of characters and stories that almost instantly trips over itself, and continues to slowly tumble down a hill for nearly 2 hours. A film that sifts through issues of human trafficking, redemption, cycles of violence, loss, family, and xenophobia, but never actually works these issues into any consistent theme or message. Crash does not say anything about the issues it brings up; rather, it only exists to get credit for simply acknowledging that these issues exist.

In one particularly offensive scene, a law enforcement officer acts out a racially motivated molestation, which is treated as a minor annoyance, and promptly moves on. It is a scene that is treated with the care and tenderness of a Darth Vader plot, rather than a disturbing real-world human violation that is allowed due to systemic injustices. By focusing on actions done by openly racist people, Crash makes it seem like these injustices are perpetrated by poorly-behaved individuals, rather than with the system that allows them to exist. In the world of Crash, systemic racism is the fault of a few bad apples.

Greenbook (2018)

Other Wins: Best Original Screenplay and Best Supporting Actor

What should’ve won: BlacKkKlansman

Greenbook sucks. It’s a lame, wishy-washy, cheesy buddy comedy that for some reason decides to take place during one of the most disturbing, frustrating times in recent history.

The film deserves credit for only one thing: the performances. They are great. But it deserves zero props for its phony feel-good screenplay, childish and simplistic depictions of systemic racism and homophobia, and capital “B” Bland direction and cinematography. As a result, Greenbook isn’t just tasteless and mildly offensive, it’s straight-up boring from start to finish.

What you see is what you get with this movie about systematized oppression directed by one of the guys behind Dumb and Dumber (not a joke). It is a perfect storm of both blandness and offensiveness that the Academy loves to honor, where they can give the big prize to a politically relevant film, but one that doesn’t make them feel too uncomfortable. This is why in 2019, the most prestigious award in Hollywood was given to a bland, artless bastardization of a true story of oppression that ultimately contorts the life of a brilliant black artist into a 2-hour reminder that “not all white people are bad”.

Its win over BlacKkKlansman is especially telling because of how they address similar themes, with the Academy ultimately going with an easy-to-swallow compromised message over a confrontational one. Greenbook is a movie made to trick the masses into thinking that they are watching something important when, in actuality, they are watching a facsimile of something meaningful. Don’t be fooled by the talented actors, this is nothing but a sanitized piece of corporate junk.

The whole movie feels like a joke, and its Best Picture win was the punchline.