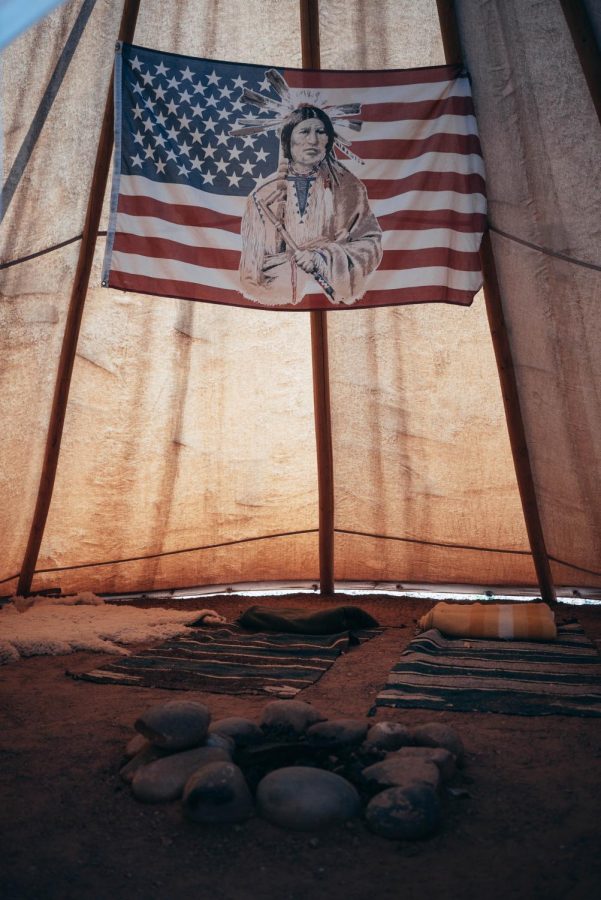

Indigenous People’s Day

October 13, 2022

The second Monday of October has been a national holiday for almost a century, but this is only the second year that Indigenous People’s Day has held that designation. Just last October, President Biden made Indigenous People’s Day a federal holiday.

Although few people are arguing with the idea of having work off on Monday, Columbus Day and Indigenous People’s Day have sparked political debates in many states and cities around the U.S. especially in the past decade with some people against this change, while others are favoring Indigenous People’s Day instead.

What is Indigenous People’s Day?

The celebrating of this holiday was established in 1977 at an international conference on discrimination sponsored by the United Nations. It is a day for honoring Native Americans and commemorating their histories and culture. The discussion to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous People’s Day began in 1990 with the International Conference on Discrimination Against Indigenous Populations in the Americas, sponsored by the United Nations. Scott Stevens, the director of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Program at Syracuse University, said Indigenous Peoples Day is about resilience of what past cultures have endured as much as it is about honoring heritage.

Where is Indigenous People’s Day Celebrated?

More than a dozen states and over 130 local governments have chosen not to celebrate Columbus Day or replace it with Indigenous People’s Day. Many states celebrate both. Eleven U.S. states celebrate Indigenous People’s Day through proclamation, while ten others treat it as an official holiday. Some tribal groups in Oklahoma celebrate Native American Day rather than Columbus Day, with some groups naming the day in honor of their individual tribes. More than 100 cities have replaced Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples Day. Stevens believes that this day being federally recognized makes it easier for more allies. “Having a federal holiday can serve as less of a celebration but more so a recognition to past and present experiences,” Stevens said. “I see (Indigenous Peoples Day) as an opportunity to have more critical discussion about our American history, more than what people learn in the fourth grade about the first Thanksgiving and Pocahontas.”