Hateful and Intolerant Speech on the Granada Campus

The Granada High community is experiencing an increase in hateful, derogatory and racially motivated speech.

February 17, 2022

The Granada high community is experiencing an increase in hateful, derogatory and racially motivated speech. This surge of intolerant language among students does not originate from one simple cause, but a multitude of factors. For many students and staff, it’s clear that this is an urgent issue at Granada, and it’s as dangerous as it’s ever been.

One incident regarding hateful dialogue on campus was in December, when a varsity boys basketball game ended in an atmosphere of threat and intimidation for the opposing school. A group of GHS students chose to express hateful, insulting and racially motivated comments toward our opposing guests, athletes and families. Following this scene, an email was sent home by Principal Hart informing the Granada community of what happened and condemned the matter by pausing student-spectators for the following two home games.

The United States is living through an age of extreme political division, and its dangerous effects are being brought on campus. Granada is witnessing harassment and violence directed toward essentially every minority group on campus, including people of color, the LGBTQ+ community, people with disabilities and various religions. Current junior and International Baccalaureate student Byrei Mott, shared multiple instances of students using the n-word during class time while her teacher continued to instruct without any course of action.

“Having attended both Livermore and Granada High, all I hear while I’m walking through the quad is n-word this, n-word that, and they know it’s wrong. And I don’t think most teachers at this school know how to react and stand their ground when hateful dialogue is put out,” Mott shared. Students like Byrei are looking for assurance that teachers and administrators are properly equipped to handle unexpected situations regarding the safety of students in the classroom.

The presentation of hateful, dehumanizing symbols at Granada have been extraordinarily pressing for many. The increase in vandalism is critical; two swastika engravings have been identified by administration and other cases have been reported since the beginning of this school year. The swastika doesn’t only symbolize hate toward the Jewish community, but people of color, LGBTQ+, disabled, and more. This is not the first time Granada has seen this symbol of hate toward minorities on campus, but students and teachers are worried about how frequent this is happening.

“There have been more incidents involving anti-Afghani intolerance, the drawing of a swastika, and an increase in the use of anti-gay slurs. The increase has been in how willing [students] are to use this kind of speech publicly, in front of others or for the presentation of others,” Mr. Hart explained.

Gia Oscherwitz, a current senior and IB diploma student, has been forced to deal with racial discrimination over her Jewish identity. For Gia, learning in an environment where experiencing hatred and a sense of fear has become a normal occurrence. The swastikas found on the Granada campus have been terrifying for her to see, and their appearances indicate the broader community’s lack of understanding of the symbol’s history and relationship to the Holocaust.

Oscherwitz has made it a priority to bring new ideas on how to initiate better communication and inclusivity over these topics. There have been disagreements as to how this situation should be handled by school authorities to integrate more conversation into the education of all students on campus.

“At the end of the day, prejudice is prejudice. This is not a debate about who is right or wrong, but a discussion about people’s lives. It should be treated with that type of weight,” Oscherwitz added.

“With all of the hatred, violence, and division present throughout our nation, we as a community need to work harder than ever to promote understanding, tolerance, and respect. Discussions of oppression and politics are not one and the same, and that distinction should be made and understood by students, teachers, and staff on campus,” said Oscherwitz.

The Granada administration and department heads are currently working on prevention and how to appropriately react when incidents unexpectedly occur. Mr. Hart leads a group called the Culture Doctors, a student discussion group that helps examine how to help make Granada a welcoming place for all student groups.

Along with the Culture Doctors and department chairs group, Hart also explained, “We do have groups external to the school that are eager to help us with resources and support, and I’m eager to get those resources to teachers and students in ways that will be most helpful to them.”

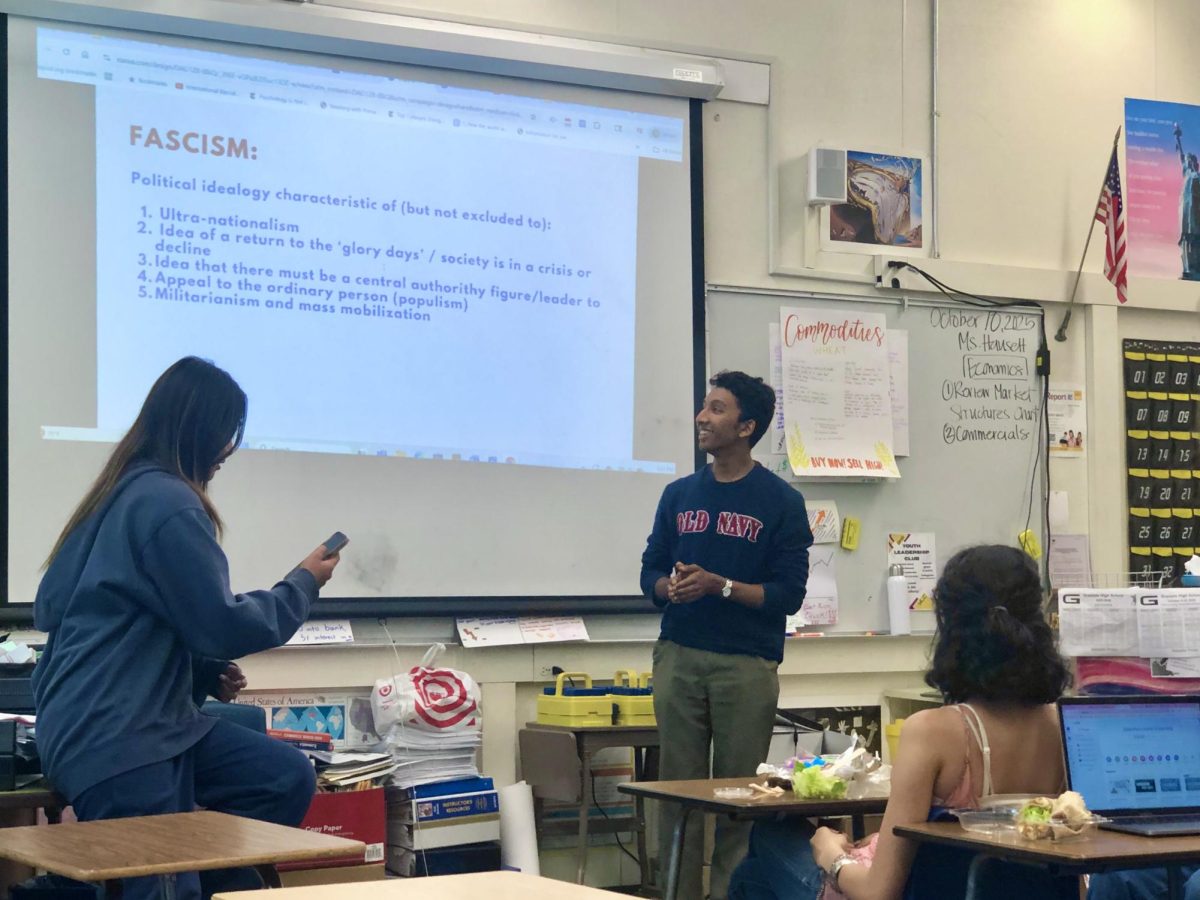

Having witnessed student intolerance first hand, Social Science and IB History teacher, Sommer Newkirk acknowledged this issue and made clear that the Social Science department speaks very openly about discriminatory actions and words.

“We make it a point to address our students on issues like tolerance, genocides, the Civil Rights Movement and teach the historical significance of different words and symbols,” said Newkirk.

With the engraving of a swastika in her classroom this trimester, Mrs. Newkirk has had a front row view of the oppressive actions amongst Granada students. “I try very hard to create a safe space for students and seeing those swastikas in my own room has been heartbreaking,” she explained.

“We also need to make sure we’re teaching students to stand up for others when they see it,” she added. As an educator, Mrs. Newkirk wants to lead inclusive conversations and relay the continuity of this situation to all Granada students.

Oscherwitz feels it’s necessary to continue promoting positive discussions. “Feeling unsafe at school is not normal and in order to bring change, students must act in starting conversations.”

serin zamoum • Feb 18, 2022 at 8:28 pm

This is so well written Wyatt

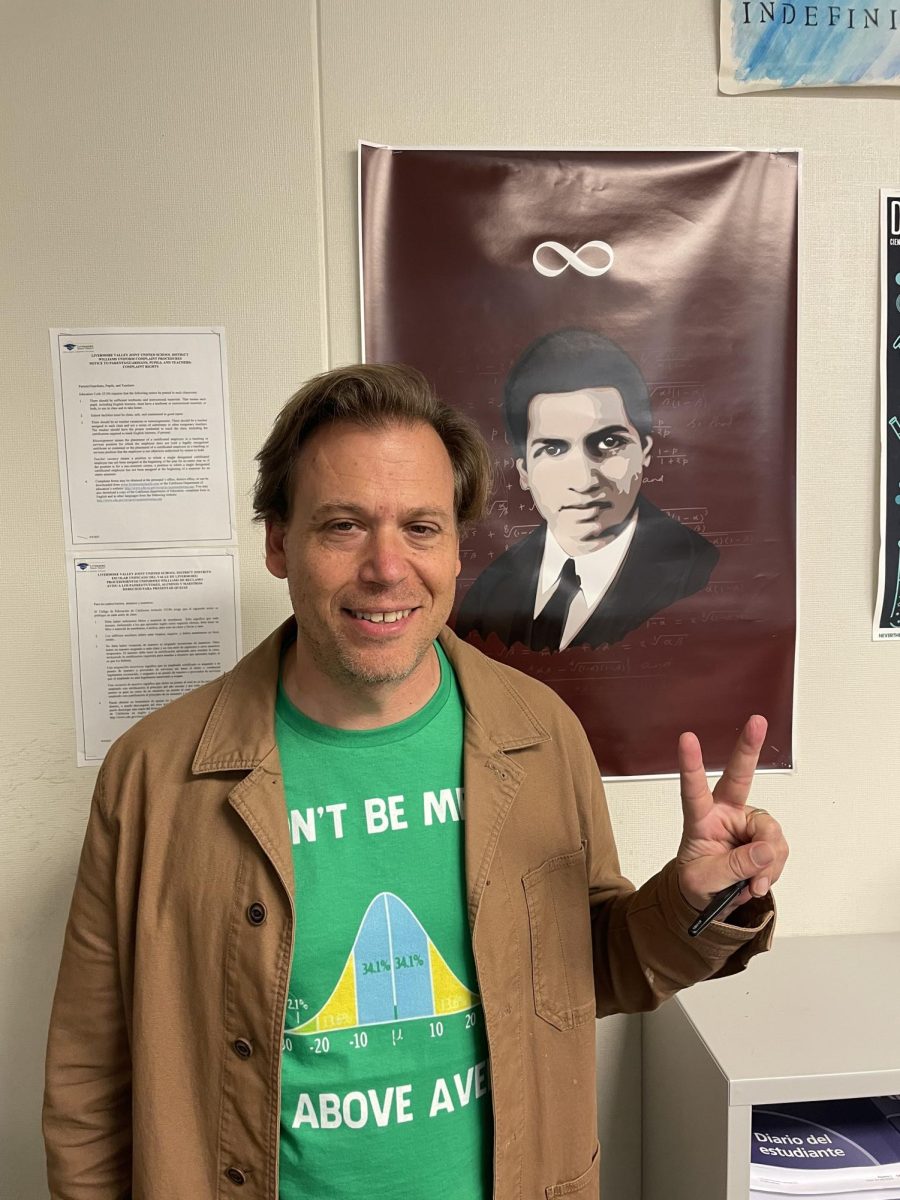

Mr. Moran • Feb 18, 2022 at 3:13 pm

Great article. Reviewed in our co-taught English classes to start the conversation.