1984 is considered by many to be the greatest year for film ever. It isn’t difficult to see why. Nightmare on Elm Street. Gremlins. Ghostbusters. Amadeus. Temple of Doom. Top Secret. This is Spinal Tap. The Natural. Paris, Texas. The list goes on and on.

This was the toughest year that I’ve done so far.

The five greatest films are as follows, judged based on artistic merit, entertainment value, originality, and modern-day relevance.

5.

Body Double

Yeah, you read that right. I seriously put Body Double on my list. I went back and forth between this film, Amadeus, and The Terminator. Ultimately, I picked Body Double because there is truly nothing else like it.

While most of the films on this list are great because they redefine what film can do, Body Double reframes what film has already done.

Before 1984, Brian De Palma’s Hitchcock inspirations were already far from subtle. However, Body Double takes it to another level.

There are two sides to De Palma’s cult classic Body Double.

The first is an ingenious Hitchcockian neo-noir thriller with a plot that ticks like clockwork. An every-man whose own twisted curiosity plunges him into the underworld of the adult entertainment industry. A sweeping portrait of Hollywood filled with garish production design, a pulsing score, and a distinct 80s excess and camp. Given how over-the-top the film is, it is shocking that it also manages to be a genuinely scary psychosexual drama. If for some reason you’ve never seen a De Palma film, I would suggest starting here. It may not be his best, but it is the quintessential example of his style.

The second side is a more complex, media-literate one. Body Double feels like a spiteful attack on the censorship boards and critics who pushed back against his ultra-violent remake of Scarface. Body Double works best as a piece of film criticism. Criticism of a system that rejects outward exploitation yet is founded upon it. De Palma argues that Hollywood is more like the Porn Industry than it would like to admit, and the Porn Industry is more like Hollywood than it would like to admit.

4.

Stop Making Sense

‘Hi. I’ve got a tape I want to play.’

After those humble opening lines, you will suddenly find yourself deep in a pool of unmatched energy. A radiant, confident, astounding trip through psychedelic performances from Talking Heads explodes in Jonathan Demme’s Stop Making Sense.

Considered the greatest concert film for a reason, there is nothing to be said about Stop Making Sense that hasn’t already been said by someone else. You have to dig deep to find any negative reviews of this movie. This film is an infectious, universal testament to creativity and passion. Like the big suit David Byrne dawns in “Girlfriend Is Better”, the body is greater than the mind.

This is the stuff dreams are made of.

3.

Streetwise

A harrowing, unfiltered glimpse into the lives of the homeless children and teenagers in Seattle. Martin Bell and Mary Ellen Mark’s heartbreaking documentary shows real kids burdened by financial problems, homelessness, abusive families, crime, drug use, and prostitution.

No matter what films you’ve seen in your life, you will not be prepared for Streetwise. The film is as harrowing in its sad moments as it is in its light moments. This is because of an unmatched vulnerability in the subjects. You’ll meet nine teens over 91 minutes, all of whom will have at least one moment burned into your brain. Patrice Pitts’ argument with the preacher. Tiny and her mother. Rat’s ode to flying.

It is difficult to review this like any other film, but it is worth mentioning that Martin Bell’s directing and cinematography and Nancy Baker’s editing are expressive, thoughtful, and intimate. Streetwise also avoids every pitfall of documentary filmmaking. It never feels indulgent, intrusive, miserable, exploitative, pornographic, or judgmental. It is an honest, unforgettable experience that leaves you a changed person.

2.

Fanny och Alexander

(or Fanny and Alexander)

Despite being polar in practice, there are a surprising amount of similarities between the top two films on this list. Both were ostensibly the final feature from a classic director (one due to retirement, the other death), are sprawling epics over three and a half hours in length, and feature multiple versions.

Now, you could make a case for Fanny and Alexander being released in 1982, 1983, or 1984. I’m going with 1984 because that is the first time Ingmar Bergman’s complete vision was shown. While the shortened version of this film is hardly the travesty that the truncated edit of the film in the top spot was, it isn’t until you see Bergman’s nearly 5-hour cut (!) that you can truly appreciate Fanny and Alexander.

This semi-autobiographical period drama mixes fantasy and realism like no other. Despite its runtime, Fanny and Alexander might be Ingmar Bergman’s most accessible work, as it features more warmth and humor alongside his typical brand of darkness. It is difficult to not get sucked into his compelling family drama, where the physical meets the metaphysical.

Additionally, if you hope to study production design, Fanny and Alexander is one of the best places to start. A single set in this film will convey more than most films do in their entirety. A detailed, unforgettable swan song for one of the greatest directors to ever do it.

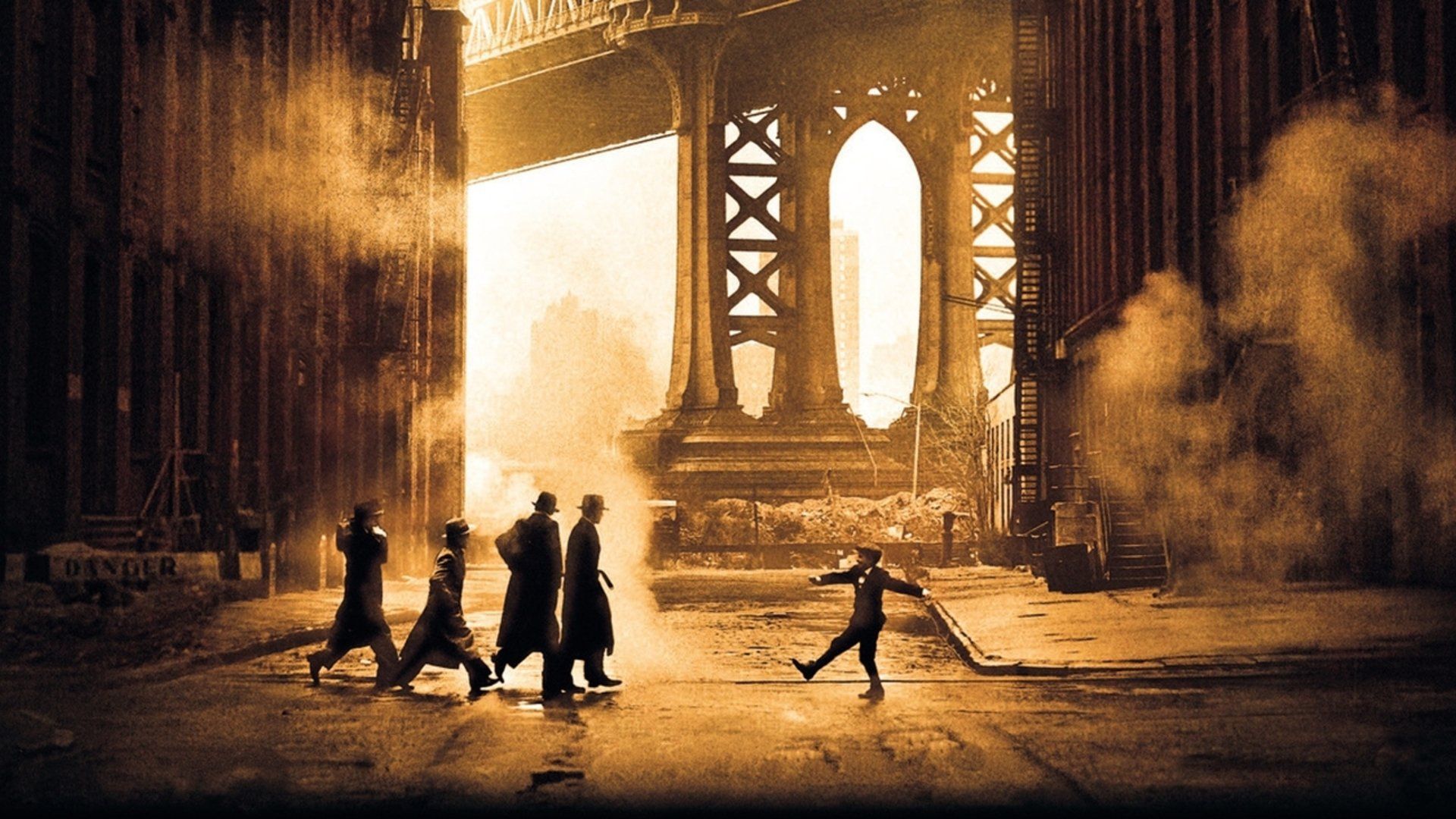

1.

Once Upon A Time In America

Here is a challenge if I’ve ever faced one: describing the brilliance of Once Upon a Time in America in a few short paragraphs. In all honesty, no amount of words could do it justice.

Coming in at just under four hours, Sergio Leone’s film is a gangster epic and then some. The film follows Robert DeNiro and James Woods, two youths from a Jewish ghetto who grow up to become some of the most twisted, brutal gangsters ever to be filmed. This is not a comfortable watch. Do not go in expecting a quotable, bloody film with darkly comedic sequences in the vein of Goodfellas or Pulp Fiction. Once Upon a Time in America is a movie that will make you angry, uncomfortable, confused, emotionally devastated, unsatisfied, violated, and disturbed. But it does this with a purpose.

Once Upon a Time in America, as its title suggests, is about the point where American Reality and American Fantasy blend. By showing his audience the absolute most dangerous rendering of the American Dream, he makes us wonder if the line between acceptable and unacceptable is thinner than we think. Yet the film is incredibly internal and subjective in a way that makes you never trust your eyes. The film contains a sequence that is without a doubt one of the most horrific and brutal that I have ever seen, yet shown through a glossy, dreamlike filter that someone would use to justify their actions.

It is an incredibly surreal experience. The film makes a choice so bold and daring, executed with such precision, that I have never seen it replicated again. There are non-linear films, but Once Upon a Time in America is an anti-linear film. While poetically transitioning between timelines, surreal anachronisms begin to pop up again and again. Even as the film’s timeline smartly snaps into place with its final scene, Leone never lets you get ahead of the movie, ending the film off with what is still one of the most iconic, infamous, analyzed, and discussed final shots in the history of film, tied maybe only by The Graduate, Fight Club, or a Kubrick film.

It isn’t just conceptually great, though. You’ve got a technically perfect experience, with fantastic performances, convincing make-up, immersive costume design, amazing editing, and breathtaking cinematography. The two heavy hitters here are, of course, Sergio Leone and Ennio Morricone, who are both rightfully considered two of the greatest artists in their respective fields. Saying that Leone delivers a perfectly directed film and Morricone created an instantly iconic and unique soundtrack goes without saying.

The film is the 16th highest-rated 80s film on 2022’s Sight & Sound list (along with Fanny and Alexander at 129), and many directors have expressed their love for it.

When discussing the film, the usually cocky Quentin Tarantino spoke with staggering sobriety and earnestness.

“He’s got the most cold-blooded, homicidal, almost psychopathic, gangsters ever. Yet, the weight of what they’re doing never rests completely in your heart. You know, the fact that you walk away talking about how beautiful the film is and how poetic the film is and how lyrical the film is and how moving the film is. It’s an incredible testament to Sergio Leone’s canvas.”

Martin Scorsese showed such an appreciation for the film that he has been working for years on finally creating a restored version of Leone’s original cut of the film with his estate.

The elephant in the room here is the movie’s various alternate cuts. If you are watching the film for the first time, make sure you catch the 229-minute version. In ’84, concerned by its gargantuan runtime, the studio re-edited the film without Leone’s input and rushed out a butchered, meaningless piece of garbage into theaters. Leone’s brilliant work of art was hacked up into a truncated, linear mess with no forward momentum or texture. Because of this, the film was robbed of almost all awards attention. For a while, the mangled version of the film was the only available copy. Gene Siskel, who was lucky enough to see the now standard four-hour cut at Cannes, deemed the original version the greatest film of 1984, and the linear version to be the worst film of 1984.

Call it irony, yet there is an undeniable trueness to the fact that the greatest, realist, most accurate depiction of America came from an outsider.