As 2023 was wrapping up, I was first proposed to the idea of talking about the greatest films from 50 years ago. This intrigued me but also scared me to some degree.

The seventies were, in my eyes, the greatest decade for cinema by a wide margin. While some great, classic films were produced in the ’60s, they mostly came from established voices such as Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, Billy Wilder, Mike Nichols, Akira Kurosawa, and Sergio Leone to name a few—all safe choices. This was mostly an era defined by many big-budget films that were expected to do well and failed spectacularly. MGM in particular had a practice reminiscent of modern Disney where, after the astonishing success of the high-budget remake Ben-Hur, they decided to put all their eggs into one expensive basket every year. And, like what is happening now with the Marvel Cinematic Universe, they got worse results every year, almost sinking them in the first few years of the decade. For a while, it seemed like cinema itself was going to implode into a series of generic disaster films—both in genre and box office result.

These failures are what led to 70s cinema, giving rise to several smaller independent creators to tell daring, innovative stories from a unique perspective. Every year a new roster of exceptional films would pop up from the most unlikely places and would end up turning a huge profit.

And 50 years ago, we got 1973, a year with no shortage of amazing, influential films. This is why selecting the greatest of that year is so daunting, not because there aren’t enough great films, but too many. As time passed, four films began to fall into the top spots with relative ease. It was the fifth place that had me stuck.

1973 had so many classic and underrated gems: including the controversial thriller Don’t Look Now, the mega-hit Bruce Lee vehicle Enter the Dragon, Martin Scorsese’s raw debut into the world of gangster film in Mean Streets, the influential folk horror of The Wicker Man, and the fantastic and underrated semi-autobiographical adult animated drama Heavy Traffic, I could go on.

That being said, a few names began rising above the rest.

The logical choice for this spot, I suppose, would be the classic American caper film, The Sting, which swept the Academy Awards that year and deserves a whole article written on its cultural impact. Or I could pick the coming-of-age dramedy American Graffiti, whose episodic structure is an excuse for stylish 60s production design, fun performances and songs, and creativity. One part of me wanted to indulge in a purely self-indulgent pick, either the blaxploitation classic Coffy which jumpstarted the always spunky and charming Pam Grier, or the 3-hour British black comedy musical epic O Lucky Man! (the second part in Lindsay Anderson and Malcolm McDowell’s underrated satirical “Mick Travis trilogy”). I even considered Woody Allen’s absurdist sci-fi comedy Sleeper to offset the otherwise grim selection. However, by a close call, I believe the film that deserves the fifth spot is…

- Serpico

For years upon years, the face of Police work in the media was a fictional LAPD detective by the name of Joe Friday. His exploits were chronicled on Dragnet, a radio series turned police procedural television drama that shaped the public perception of police officers as skilled, heroic men putting themselves in danger for the greater good. This line of thinking would not make it through the rise of the counterculture crowd and would crumble for many during the Watergate scandal.

In 1971, two of the most talked about films were about “bad cops”, The French Connection and Dirty Harry. Both of these films were revolutionary because, for the first time, audiences saw a corrupt law enforcer working outside of the system.

All of this context is part of what makes Serpico such a bold, different piece of art. The film is based on real-life NYPD detective and whistleblower Frank Serpico, played here by a post-The Godfather Al Pacino. Frank is not a corrupt man working in a good system, he is a good man working in a corrupt system. By returning to a Joe Friday-esque protagonist, Sidney Lumet’s film paradoxically paints a much darker, scarier picture of the modern world. By doing this, the film not only brilliantly tells Serpico’s story, but also serves to prove his ideology in a way that only cinema can: by showing that the Police Department is made for the Dirty Harrys of the world.

Whether or not you agree with the film’s politics, it is undeniably relevant in today’s world.

But all of this would mean nothing if Serpico wasn’t a compelling drama on its own. However, these larger themes are just part of a complex, thrilling film. Sidney Lumet directs with a fast, uneasy feeling that reflects Serpico’s isolation. One of the most noteworthy elements of Serpico is its editing, courtesy of Dede Allen. The film purposefully toys with reality and linear progression, as some moments are played in agonizing realtime, while years will pass in seconds. It is sort of a grittier version of the storytelling Sergio Leone would later use in the American greatest genre film of the 80s, Once Upon a Time in America.

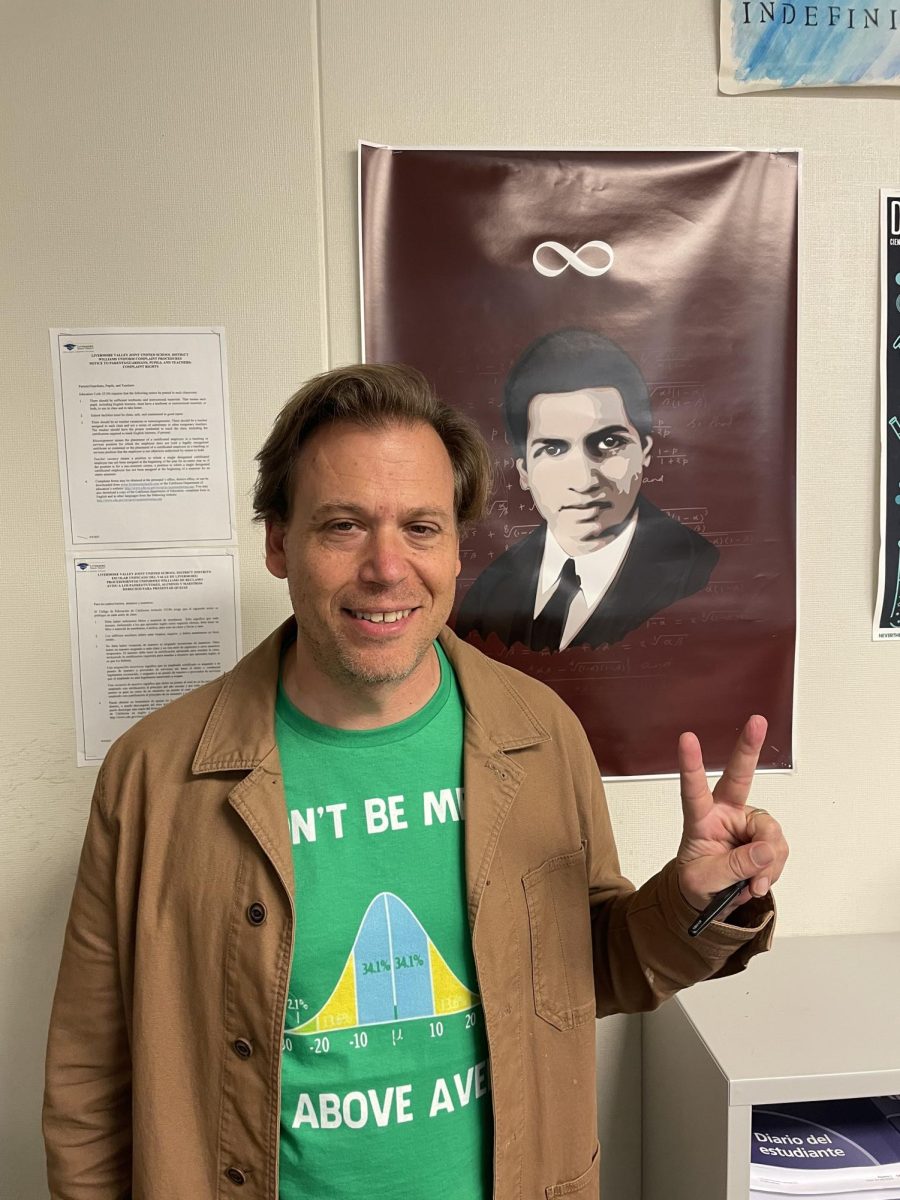

And, of course, Serpico cannot be properly discussed without bringing up the fantastic performance of Al Pacino as the title character. In the second year of his hot streak in the early 70s, Pacino’s equal parts vulnerable and gritty performance in Serpico earned him (along with a BAFTA, Golden Globe, and National Board of Review nomination) his second of four consecutive Best Actor nominations at the Academy Awards.

So, despite some steep competition, Serpico is my pick for the fifth greatest film of 1973. Until we live in a world where its themes aren’t more and more relevant with each passing year, this will remain a disturbing, edgy, and unflinchingly honest masterpiece.

- La Planète sauvage (or Fantastic Planet)

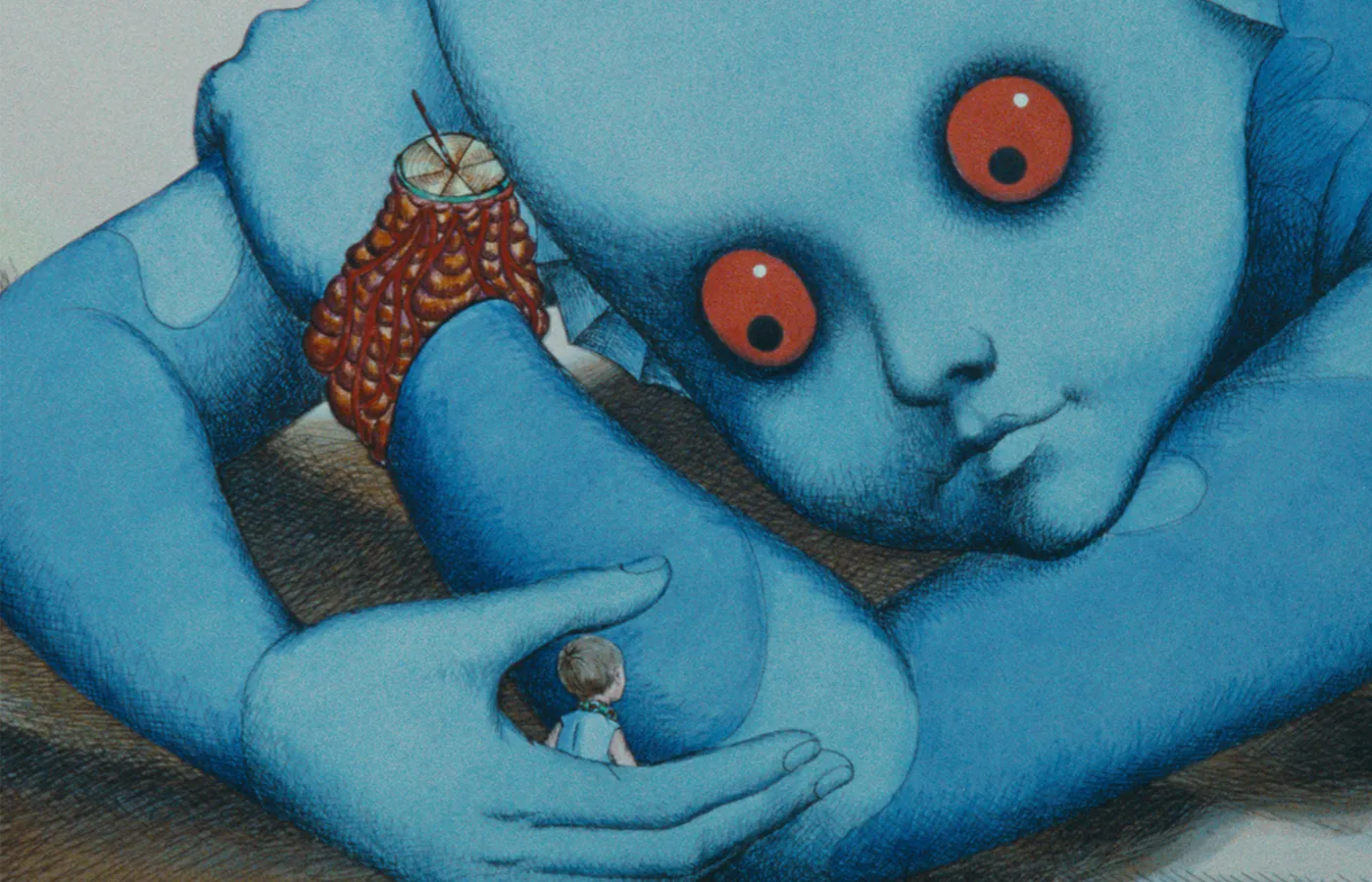

For better or for worse, there is only one Fantastic Planet. From the minds of Roland Topor and René Laloux, based on a short story by Stefan Wul, Fantastic Planet is a mature and deeply experimental French animated allegorical science-fiction/fantasy art film. A co-production between France and Czechoslovakia, the film follows humans being domesticated pets to a species of highly evolved, giant blue creatures native to the planet Ygam.

The film is definitely a looker, with stunning production design and concepts. The animation isn’t exactly smooth, but its rough aesthetic and psychedelic imagery fit the disorienting tone of the film perfectly. It also features a memorable soundtrack composed by jazz pianist Alain Goraguer, which is very evocative of the psychedelia art and music scene of the time. The music has a Pink Floyd vibe.

Fantastic Planet has a lot to unpack, with themes of animal rights, human rights, and xenophobia. Don’t be fooled by the animation, the sci-fi, or even the PG rating: this film is not for young audiences, who would have trouble understanding the allegory at play. But for the sophisticated viewers, it’s a trip worth taking at least once.

- The Friends of Eddie Coyle

The Friends of Eddie Coyle is a criminally good time, directed by the underrated Peter Yates. Taking the talented Robert Mitchum, one of the biggest faces of the Film Noir era, and recasting him as an aging low-level Boston gangster was a risky move that paid off with flying colors. His performance is as wry, rugged, and thoughtful as the film itself is, as well as both sharing a healthy dose of ironic cynicism. It’s a very 70s movie.

The film’s plot is laid out uniquely, and despite not being tied to his perspective, we learn information as Eddie does. Let’s just say there are some difficult choices he has to make, small scale and large scale.

Based on Paul Monash’s novel of the same name, the film’s commitment to realism and credibility doesn’t stop it from being one of the most compelling character studies. Beyond the stand-out performances, the film has a tight plot, some tense scenes, and manages to be impossible to predict from beginning to end. This feels like Peter Yates’ Jackie Brown, a slower, darker, more mature picture from a director known for delivering crowd-pleasers.

- Viskningar och rop (or Cries and Whispers)

Pain. It’s hard to watch Cries and Whispers without feeling some kind of vicarious pain for the women on screen. The Swedish period drama, only the fourth foreign film to ever be nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards, was the creation of the acclaimed director Ingmar Bergman. Harriet Andersson, Ingrid Thulin, and Liv Ullmann play three estranged sisters in the late 19th century whose relationship with each other and their longtime servant is tested when one begins slowly dying from uterine cancer — yeah, it’s a bit of a rough watch.

The film is pure cinematic magic. It may not be Bergman’s greatest work (Persona is my vote), but it is probably his most haunting. The film moves like no other, drifting forward and back in time, moving in and out of surrealism, not for context or plot, but for emotional weight and meaning. It is also one of the few films from the director to use color, with Sven Nykvist’s staggeringly gorgeous cinematography and Marik Vos-Lundh’s ruby production design.

In Cries and Whispers, Bergman continues his long history of writing female characters like almost no other men were at the time. Instead of creating them to serve simple roles, he builds complex characters out of his own fears and morphs the story around them. In a time when most directors were still getting away with archetypal depictions of women, Cries and Whispers was a uniquely progressive tale. The film does still feel like the work of a man, but one with unprecedentedly empathetic and open views on maternal estrangement, emotional suppression of women, sexuality, and gender roles.

- The Exorcist

This one isn’t exactly unknown. The Exorcist is as iconic as films get. Imagery from this movie has been burned into the public consciousness more so than any other film from the decade. After her 12-year-old daughter (Linda Blair) starts acting strange, a mother (Ellen Burstyn) has to go to some unconventional routes to bring her back. One of the most defining films in the horror genre plays out like a grounded psychological drama, making the supernatural elements shock like none before or arguably since.

The film was one of the biggest and most publicized releases of all time, and dramatically changed the way the genre of horror is viewed in the eyes of the public. For a long time, with a few exceptions, horror was still The Wasp Woman or Reptilicus; cheesy, forgettable camp that will pass the time, nothing else… the antithesis of The Exorcist.

The Exorcist is unforgettable, sad, sacrilegious, and disturbing. There were protests against it, protests in support of it, countless references to it across all of pop culture, and constant press.

The New York Times reported that “once inside the theater, a number of moviegoers vomited at the very graphic goings‐on on the screen. Others fainted, or left the theater, nauseous and trembling, before the film was half over. Several people had heart attacks, a guard told me. One woman even had a miscarriage, he said.”

But beyond all the blasphemy, shocking imagery, perversions, and gore: The Exorcist more than earns its place as a staple of the horror genre. The first of very few horror films to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture (one of only six in almost a century of existence), and winning Best Adapted Screenplay, the film premiered as a classic and it lives on as such today. This is not only the best film of 1973, not only one of the best films of the ’70s but one of the greatest, most powerful films of all time.